Editor’s note: See Leuner, Kirstyn J. “Locating Women’s Book History in The Stainforth Library of Women’s Writing.” Studies in English Literature 1500-1900, vol. 60 no. 4, 2020, p. 651-671. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/sel.2020.0026. It provides added theory, detail, and context to the project rationale drafted here.

&

Francis John Stainforth (1797-1866) was a British Anglican curate and a collector’s collector of stamps, shells, and most of all, books. He curated what we have found to be the largest private library of Anglophone women’s writing in nineteenth-century Great Britain. His library catalog lists 7,122 unique editions (over 8,000 volumes) authored and edited by more than 2,800 writers, nearly all of whom are women. He left scholars a rich trace of his bibliographical enterprise in a 746-page library catalog manuscript. To grasp the size of this library, consider that Stainforth’s collection was comparable in size to, if not slightly larger than, the 8,000-volume collection of books by women showcased in the Woman’s Building Library at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (Wadsworth 84).

When we think of 19th-century private libraries in Britain, we usually envision a gentleman’s library like the one Jane Austen’s brother Edward kept at Godmersham Park. Shelved in an English countryside estate, the library contained works mostly in English and Romance languages written by men in the genres of biography, history, geography, theology, literature, and travel writings. Stainforth’s library rejects this patriarchal model and makes a political claim that women—struggling working mothers, women of color, disabled authors, translators, children, aged writers, Jews, incarcerated poets, printers, schoolteachers, women who co-author with their husbands, survivors of assault, hymnists, those who publish only a single poem, and more—have a valued place in book history and on the shelf. He collected works by women writers not only from Britain but from America, Australia, Canada, and Asia who published between 1546 and 1866. His project, according to his catalog, was to collect a copy of every edition of every title by women poets, dramatists, and nonfiction writers before his death in 1866.

The Stainforth DH project recovers this activist library and simultaneously draws attention to the near disappearance of a richly diverse and populous women’s book history and literary history.

The Library Catalogs: An Auction Catalog and a Manuscript Catalog

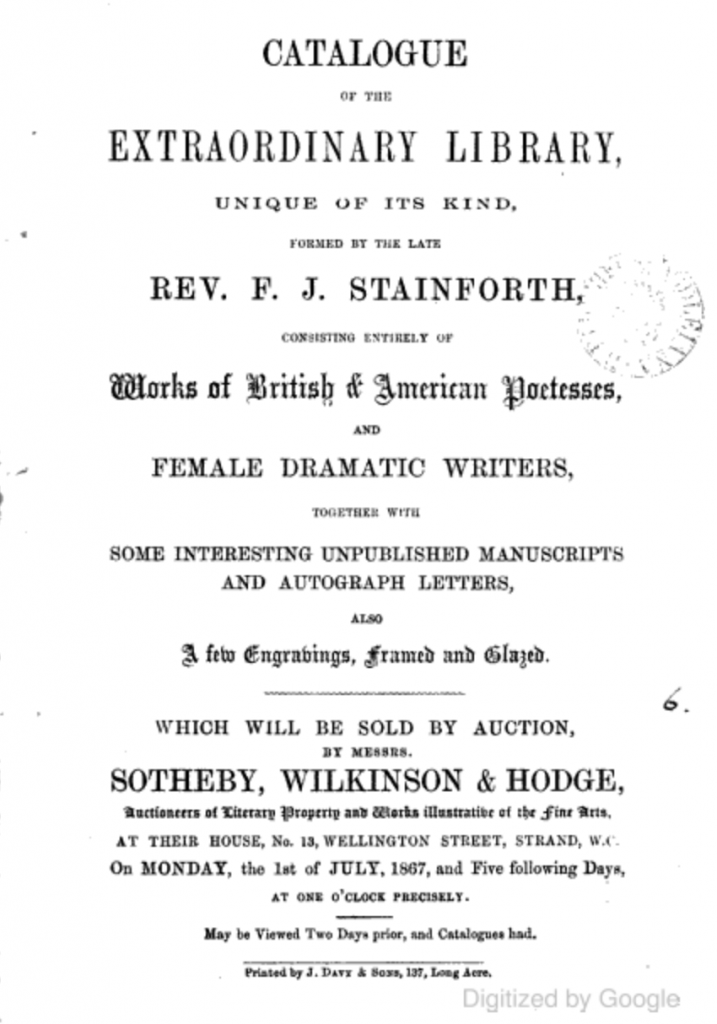

The manuscript catalog at the heart of the Stainforth Library digitization project has been historically eclipsed by the auction catalog for the library, published in 1867. After Stainforth died in 1866, his family left the rectory they inhabited at All Hallows Staining, and the auction house Sotheby, Wilkinson, and Hodge took possession of his library. Among the books on the auction block was his very own library catalog manuscript. As with every auction, the auction house created a catalog of the items for sale each day to advertise the items and the event to interested buyers. “An auctioneer’s catalogues are all important: they are the firm’s ambassadors, salesmen and recording angels all in one,” and this was especially true of Sotheby’s, which has even been accused of over-cataloging (xvi Hermann). The auction catalog for the Stainforth library tells us that the auctioneers divided the library into 3,076 lots to be sold over six days starting on July 1, 1867. The catalog is organized by day of the auction (days one through six) and by ascending lot numbers, where lots are organized roughly alphabetically by author last name, starting with printed matter by A. (C. E.) Grace and Glory delineated (1855). The last day of the auction concluded with the sale of Stainforth’s “fine engravings” and manuscripts, including his library catalog. The entire library sold for a total of 792 pounds and 5 shillings, with Thomas Bentley’s 1582 edition of Monument of Matrons winning the highest price at 63£ (Sale Catalogues, 14).

The auction catalog advertises Stainforth’s books in a manner meant to sell this library to pieces. Like any good sales pitch, it emphasizes the product’s most attractive aspects, and it downplays the rest. Most lots contained groups of works to help attract buyers to titles that may not sell on their own. Additionally, the auction catalog annotates the most valuable titles to highlight their desirable features, and it does not annotate other titles.

The auctioneers also mischaracterized the library to attract buyers. They titled the catalog Catalogue of the Extraordinary Library, Unique of Its Kind, Formed by the Late Rev. F. J. Stainforth, Consisting Entirely of Works by British and American Poetesses, and Female Dramatic Writers, Together with Some Interesting Unpublished Manuscripts and Autograph Letters, Also a few Engravings, framed and Glazed. Though long and detailed, the title is inaccurate. Stainforth did not limit himself to works by British and American poets and playwrights; he collected a wildly diverse range of genres beyond verse and drama. There are even examples of male authors in his library, especially where they coauthor or co-edit with women. Moreover, the auctioneers incorrectly portrayed Stainforth’s project to collect women’s poetry, drama, and non-fiction prose as “complete.” They made it appear that all of British and American women’s poetry and plays have already been collected and cataloged in total, by Stainforth. They celebrate the herculean efforts of the collector to curate such a library rather than the intellectual labor of the thousands of authors represented in his library catalog. Nevermind that many of the authors Stainforth collected were still writing after he died in 1866. Sotheby’s advertising hoped to create a mystique around Stainforth’s project so that buyers would see value in purchasing a part of “the Stainforth library” even if the value of women’s writing, on its own, was less significant.

The Legacy of the Auction Catalog

The published auction catalog and its myopic and uncharacteristic portrayal of the library enabled scholars and the press to hijack the narrative of Stainforth’s project and relay it as a story of the catch-and-release of all of women’s writing. For example, in 1883, The Woman’s Journal ran a feature story by “T.W.H.” about Stainforth’s library on the front page. In the article, the auction catalog stands in for the actual library, and the author treats the catalog as data that produces a new conception of the scope of women writers’ contributions to book culture. The author explains that she sits with the auctioneers’ catalogue before her and marvels at the collection with language that treats it not only as a library, but instead as a “vast and singular monument of the literary industry of English and American women” (TWH 297). Like the auctioneers, and perhaps due to the auction catalog’s title and preface, she also miscommunicates that Stainforth’s collection only contains poetry and drama. The author then uses the auctioneers’ catalog to quantify and measure the library. She guesses that the catalog must list 7,000 volumes in the library, and “there are no less than 150 volumes by Miss Hannah More; 94 by Mrs. Elizabeth Rowe, once famed as “Philomela;” 79 by Mrs. Hemans; 66 by lady Mary Wortley Montagu; 61 by Mrs. Inchbald; 38 by Mrs. Maclean (L. E. L)” (TWH 297). Quantification goes hand in hand, for the author, with the collector’s “thoroughness”: “There is something extraordinary in the care with which whole series of editions were brought together by Mr. Stainforth; for example, the nine successive issues of the once famous poems of Charlotte Smith” (297). Stainforth’s sizeable auction catalog coupled with his assiduousness in collecting authors’ works as well as runs of editions leads the author to comment on the purpose of Stainforth’s library:

it would seem an infinite pity that it should have been dispersed; were it not that it is the mission of private libraries to feed public ones, and that this may have passed into some collection that may yet be made even more complete, and perhaps permanent. (297)

Stainforth’s Personal Manuscript Library Catalog

The manuscript library catalog stands in stark contrast to the Sotheby’s auction catalog, which misrepresents the library as Stainforth describes it in his catalog and related materials. One of the goals of the Stainforth Library of Women’s Writing digital project is to correct these long-standing mischaracterizations of the limited diversity and depth of women’s writing in Stainforth’s library by offering the searchable manuscript catalog and supporting research as counterpoints of evidence. You can find a detailed bibliographical physical description here.

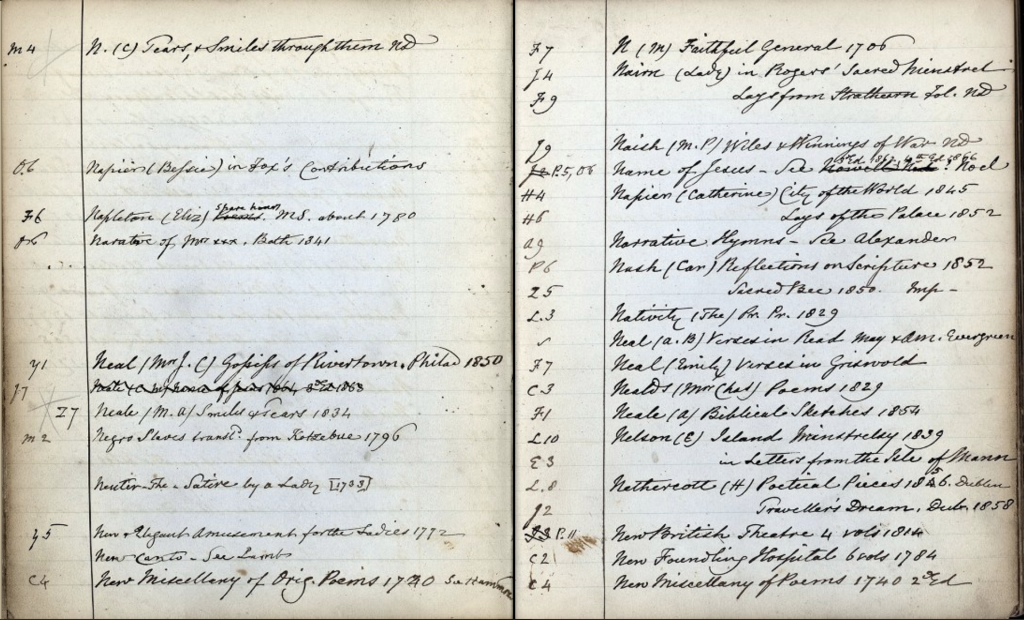

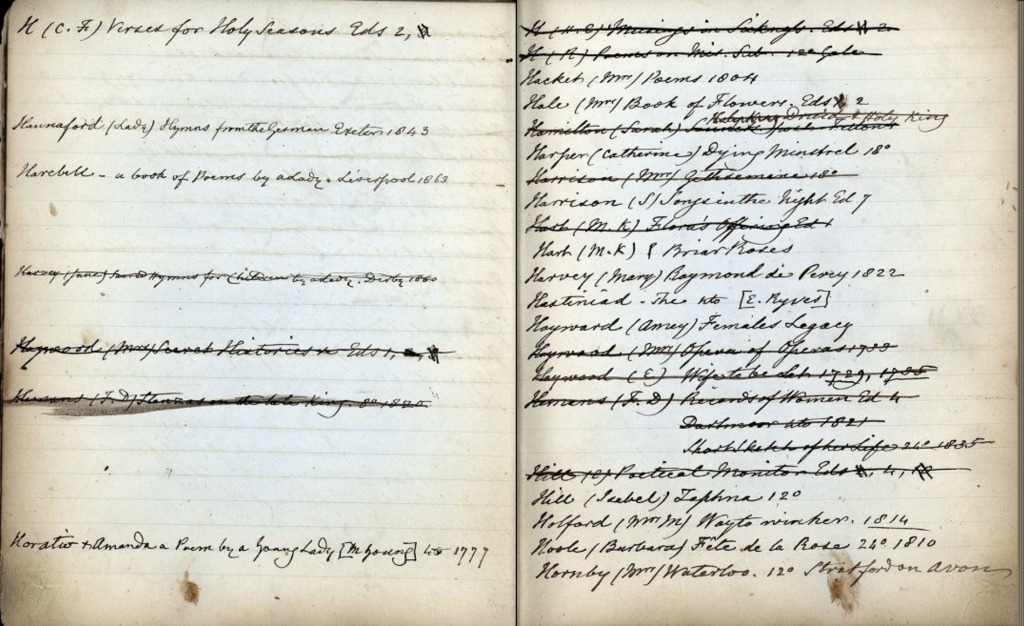

The handwritten catalog is a very thick quarto account book of 746 pages, where pages 1-509 list holdings and pages 510-746 show his wish list of books to acquire. He lists all of the works in his holdings in alphabetical order by author last name, or by title where there is no author listed. Almost every entry starts with an alphanumeric code that we interpret as a shelf mark that denotes how he ordered his books. Next, he lists author last name and first name, an abbreviated title, edition information, and pub year. He occasionally lists publication place, format (e.g., folio, octavo, manuscript), if a work was privately printed, and if it contains an author portrait or plates. In the holdings section, he also cross-references names and titles to create a finding aid that, for example, helps a user find the title “The Buried Bride” under the last name “Ward.”

The Wants catalog, which is not in the auction catalog, is a crucial part of Stainforth’s library project and the Stainforth Library of Women’s Writing searchable digital edition. Not only does it list some of the rarer works by women in the nineteenth century, it is also a key to understanding Stainforth’s acquisition processes and values as a bibliographer. The “Wants” section, or wish list, also organizes its titles by author last name, however these entries are less formulaic and data-rich. The Wants catalog is also slightly harder to read because many of the entries have lines or hash marks through them. When Stainforth acquired a book listed in his Wants catalog, he crossed it off and, sometimes, added it to the holdings catalog, which was conveniently attached by the same spine.

To find the start of the Wants list in the manuscript, you must flip the book 180 degrees on its spine so that what was the back cover is now on top, with the spine on the right. Then, rotate the book so it opens, once more, with the spine on the left. This is the hallmark of a tête-bêche, or head-to-toe book format. The Oxford Companion to the Book describes it as “a type of binding, gathering two books, with one bound upside-down relative to the other.” While Stainforth might have crafted his catalog tête-bêche to save paper or just to stay organized, this format has additional significance as it relates to stamp collecting. Stainforth would certainly have been familiar with it, as he was a well-known stamp collector who helped establish the Royal Philatelic Society of London. The Stamp Collector’s Magazine describes the tête-bêche to beginner collectors as a valuable printing error:

produced by the insertion of one of the casts wrong side up in the frame, so that, relatively to the surrounding stamps, the stamp is upside down. In order to show this accidental variety, it is necessary [that] the tête-bêche should be preserved by the side of its neighbor. The two stamps should be cut out together from the sheet, and of course must not be separated from each other, or the wonder ceases, for the tête-bêche derives its value simply from the position in which it lies relative to the other stamps. (“Newly Issued”, 10)

Stainforth would have known about the famous series of stamp printing errors in France between 1849 and 1866 that introduced hundreds of thousands of tête-bêche pairs—some of which appear in Mount Brown’s revered 1862 stamp catalog that Stainforth helped compile. As the magazine quote emphasizes, the value of the tête-bêche resides in keeping the perforation between a pair of stamps and treating them more like leaves joined by a book spine, as this enables one to see the rare inverted orientation of one of them.

This manuscript format is significant because it characterizes the authors and titles on Stainforth’s wish list as part of his library catalog. While tête-bêche stamps were usually printing accidents, according to the Stamp Collector’s Magazine, the format of Stainforth’s library catalog appears to be intentional. This is to remark that for the Stainforth catalog, the tête-bêche conjoining his holdings and wish list catalogs augments the value of the wish list to that of an organized sub-catalog of its own and part of Stainforth’s greater catalog and library project. The collector carefully organizes the Wants catalog such that it mimics the holdings catalog with entries in alphabetical order by author last name or title. Further, Stainforth breaks this back catalog into sections: poetry and drama by British authors, then a section for “American Writers,” then a section devoted to “Plays Wanted,” and finally a list of desired literary annuals. Even those titles with no strikethrough—those that he did not obtain—are part of the Wants catalog and his library. In fact, a stamp collector like Stainforth would argue that the inverted and attached Wants list is a rare component that makes the entire catalog more valuable.

Why Create a Digital Edition of the Manuscript? Why TEI?

A new edition of the manuscript catalog must be digital. At 746 pages–divided into 2 main sections (holdings and wants) and then subsections within those, and including 677 cross-references, 7,122 editions and over 2800 writers–the catalog is too large and complex to process without the help of computing to reveal an accurate scope and variety of its contents. One must be able to both search and browse the manuscript in digital page images. The searchable edition of the library catalog critiques narrow literary period-specific and discipline-limited views of literary and book histories and feeds interdisciplinary research, across four centuries in the fields of literature, women’s and gender studies, bibliography, religion, music, race studies, and more. The digitized catalog enables searches by keyword, section (holdings catalog or wish list), shelfmark, author, title, date range, publication place, publication date, format, if the book was privately printed, if the book contains plates or portraits, and if the title is struck-out in the entry. In the coming phase of the project, we will add more search capabilities, such as genre.

TEI encoding Stainforth’s manuscript formally preserves, in XML, the structural and topical components of his catalog as he organized it. TEI encoding assists in the display, electronic publication, and searchability of the edition. It promotes dynamic visualizations of the complexities of the text, where a narrative argumentative peer-reviewed article can only describe these features and a print edition of the catalog would have very limited searchability.

Works Cited

H., T. W. “The Stainforth Library.” The Woman’s Journal 22 Sept. 1883, p. 297. Nineteenth Century Collections Online. https://link-gale-com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/VZPDBW306505547/NCCO?u=coloboulder&sid=NCCO&xid=54392b92. Accessed 4 May 2020.

“Newly Issued or Inedited Stamps.” The Stamp-Collector’s Magazine, vol. 12, 1874, p. 10. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/ELEEAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0. Accessed 4 May 2020.

Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge. Catalogue of the extraordinary library, unique of its kind, formed by the late Rev. F.J. Stainforth. London, J. Davy & Sons, 1867.

Stainforth, Francis. Catalogue. [In a later hand:] of the library of female authors of the Rev. J. Fr. Stainforth, [Before 1866]: 65.20, WPRP 290, University Libraries, Univ. of Colorado Boulder.

Wadsworth, Sarah, and Wayne A. Wiegand. Right Here I See My Own Books: The Women’s Building Library at the World’s Columbian Exposition. Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2012, p. 84.