This page includes documentation of our editorial principles and methods. If you have any questions or would like to learn more, email kleuner [at] scu [dot] edu.

Statement of Our Collaborative Ethos

The Stainforth Library of Women’s Writing would not exist without the contributions of many editors since the project’s beginnings. The project team will remain committed to the feminist editorial principles of

- inclusive collaboration,

- proper attribution of work (where the definition of “work” is fluid),

- transparency of our editorial processes, and

- preserving the scholarly integrity of our data and the project as a whole.

Our collaboratory methods include working together in person when feasible, but because the team is split between multiple institutions, we usually work remotely. To raise questions and discuss solutions in real-time, we use Slack for internal communication with the team. We also use Twitter to pose our questions to a larger public audience of intellectuals who can approach our queries with fresh eyes and an array of expertise. We invite conversations about the project with the widest range of public intellectuals on social media and in person.

The project began in 2012 as a collaboration between Kirstyn Leuner, Deborah Hollis, and Holley Long in University Libraries at the University of Colorado Boulder. Collaborations between CU-Boulder, Dartmouth College and, beginning in Fall 2017, Santa Clara University are a consequence of the project director being employed full-time at those institutions after completing her PhD at CU-Boulder, first as a postdoctoral fellow in the Neukom Institute of Computational Science and, subsequently, as Assistant Professor of English at SCU.

Generous funding and support of many varieties has been provided by: an Innovative Seed Grant (CU-Boulder); The President’s Fund for the Humanities (CU-Boulder); Special Collections and Archives (CU-Boulder); The William H. Neukom Institute for Computational Science (Dartmouth College); the College of Arts and Sciences, the DH Working Group, and the library at SCU. For a list of our current and former contributors, see our About Team Stainforth page.

We adopted a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license. We hope that you will use our project to explore the Stainforth library and learn more about this important nineteenth-century private library of women’s writing and its contents. We also encourage scholars to conduct their own research and publish digital or non-digital scholarship on the Stainforth library. According to our CC license, you are free to “copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format” and “remix, transform, and build upon the material” as long as you:

- Give appropriate credit and cite the Stainforth project. See our “how to cite” page for help.

- Use the same license we do (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) and provide a link to this license, so that subsequent work will again use the same license.

- Use the material for non-commercial purposes.

Project Overview & Short Technical Description:

For a technical description and overview of the digital project, see this blog post. For the whole nine yards, read on.

Transcription

Our overall editorial goals are (a) to faithfully represent and share the bibliographical data that Stainforth cataloged in his manuscript, and (b) to make these data searchable and create awareness of the greater scope of women’s literary and book histories. This project is not a detailed study of the manuscript itself, thus we have not transcribed and encoded every mark or space in the manuscript.

Before we began transcribing, we scanned the manuscript because Special Collections determined that the book was already too fragile for frequent handling and manipulation. We assigned each line in the catalog a unique identifier so that we could track transcriptions. Thus, we scanned the catalog in high-resolution images, and then created a PDF file for each page that labeled pages with a page number and also numbered each line of each page. There are 746 pages, and each page has 24 lines per page, with a few exceptions. The library IT technicians working on the project in 2014 sadly did not leave documentation of their precise resolutions, but an examination of the files by CU Libraries IT in 2022 suggests they were shot at 600 ppi, 24-bit color, interior text was shot at 600 ppi, 8-bit grayscale, and all individual pages, including covers, were saved as individual TIFFs.

After creating the lined and numbered PDFs, the team set about transcribing the entire catalog page by page, line by line. It was a painstaking process that required the work of nine editors over three years. Before the transcription process started and during the work, a complex set of Guidelines took shape in the team’s Google Drive folder that established mutually agreed upon editorial rules for how the team would consistently treat the data. For example, our guidelines specify that where data is unreadable due to damage (torn pages, spilled ink, etc.), we include tags around the damaged text with x’s to denote missing characters and that the type of damage be recorded in the notes field for the line. These guidelines also cover how to deal with incomplete data, unreadable data, deleted entries, or entries with data added above or below the line, for example. Guidelines further include rules for what data types to enclose in specified tags that accord with the Text Encoding Initiative P5 Guidelines. All of this was done to ensure transcriptional fidelity with Stainforth’s original entry and consistency among an evolving group of collaborators.

For each page of the manuscript, editors created a new Google Sheet from a template and transcribed the manuscript line by line according to our guidelines. This process could be as easy as noting that every line was blank or could be an involved process requiring extensive research and consultation with other editors. Some transcription puzzles were even solved with the help of crowdsourcing solutions on Twitter. The resources we used most often for transcription research include the Sotheby’s auction catalog, worldcat.org, The Orlando Project, Google Books, Internet Archive, and HathiTrust.

Before an editor could begin work on a page, they would “sign” that page out on a tracking sheet maintained in Google Drive. Most editors signed out blocks of approximately ten pages at a time. This same tracking sheet template was use during the editorial process as we double checked each other’s work.

We transcribed each line from left to right across the page, preserving Stainforth’s spelling, punctuation, style, abbreviations, spaces (though not the exact dimensions of the space), and other marks that pertain to the catalog’s content. For example, where Stainforth uses “Xtn” to indicate “Christian,” we transcribed the abbreviation as is. We separated entities where necessary by a single space. For accented letters and nonstandard characters, we use the actual character rather than a character entity reference, where possible; nonstandard characters, like checkmarks, are represented as HTML character entity references (this is a change from earlier guidelines). All but a few of the pages have 24 lines. We assigned line 1 to be the first entry at the top of the page where the first ruled line appears. A few pages have 25 or even 26 entries with entry/line 1 appearing above the topmost ruled line.

- View our guidelines for transcribing here. [Note: these were our raw working/evolving guidelines for the project team. They have not been polished.]

Editing

Once each line of the manuscript was transcribed, the team began editing the data in stages. We save raw transcriptions in a separate Google Drive folder and edits made to our transcriptions in new files so that we (a) had backups of our data and (b) could compare the original or raw transcription with the edited version if needed.

The complete editorial process involved comparing our transcription to the manuscript in three different phases. If we found a discrepancy, we would communicate as a team via email or Slack to get confirmation from at least one other team member on our proposed change. Phase 1 confirmed the shelfmark transcriptions and edited for interlines—places where Stainforth wrote an entry between two lines. In phase 2, we looked solely at content to ensure no information was missing from the body of the transcription. In phase 3, we reviewed our TEI tags to check for any errors. The purpose for editing in multiple phases was to focus our attention on one aspect of the data at a time and thereby create a more accurate and streamlined editorial process. (We discovered that trying to do all of these editorial tasks at once led to too many human errors.) After these three phases were completed, we spot-checked every 10th line (about 2 lines per page) and revisited challenging areas. In an effort to ensure that our data is as clean as possible, we include feedback forms below our published transcriptions to crowdsource edits to human error that we did not catch in our review despite our best efforts.

- View our transcription editing checklist here. [Note: these were our raw working/evolving guidelines for the project team. They have not been polished.]

After every page had been thoroughly edited, we compiled all of our data (each ms page had its own file) into two “master” spreadsheets with all pages combined: one “master” for the acquisitions side of the catalog (Stainforth’s holdings) and another one for the “Wants” catalog, or wish-list in the back of the catalog, which was transcribed during the same initial phase. At this stage, we needed to further edit our data in preparation for parsing it. This involved assigning an Entry Type (such as “AuthorOnly,” “Title Only,” “Blank”) to each line of data. For example, most of Stainforth’s catalog entries include an author and a title, and these lines would therefore be labeled with an “AuthorTitle” entry type. The parser separated the data in each transcription into distinct columns. These include shelfmark, author, title, publication place, publication year, and book format.

The Parsed Data

Once the parser sorted our data into the necessary columns that would ultimately form the beginnings of our database, we edited it once again to eliminate parser errors. We also had to ensure that data was represented consistently throughout the database. For instance, Stainforth’s primary method of listing authors is by last name, first name or initials in parenthesis–e.g., “Bronte (Charlotte)”. If an irregular line had brackets around a name instead of a parenthesis, or if Stainforth listed the surname last instead of first, we changed it manually in the AuthorText column but left the transcription so that it accurately reflects the manuscript.

The edited transcription data exists in two formats in our database: (1) as a replica of the data as it appears in Stainforth’s manuscript on each line, and (2) with that same data parsed into unique fields. To increase searchability, we edited some of the data after they had been parsed into multiple fields. We did not make any of these changes to the original transcription entry field – these remain untouched except for when we correct transcription errors. In the parsed fields of data:

- We removed the punctuation from shelfmarks.

- For the many entries that list an unidentified text in a named collection, we reordered the title to favor the named collection. For example, where Stainforth lists the title “Hymn in Muggleton,” we reorder the title entry to read “Muggleton, Hymn in” to emphasize the part that leads to the title Divine Songs of the Muggletonians, since we cannot easily discern which hymn it is in the collection. Similarly, in the rare case that Stainforth put “The” before the rest of the title instead of after it, we moved the article. For example, “The Shrine” was edited to “Shrine, The”.

- Edition and volume numbers are also listed in a regularized fashion in the separate Title field. For example: “Letters + Poems. 3rd Ed”, “Voices of Xtn Life. 2nd Ed”, “Posthumous Works. 2 Vols. 2nd Ed”.

Database

Finally, with the help of our programmer Chad Marks, we developed a custom MySQL database with back-end user interfaces for project editors and administrators. We assigned each field in the database a TEI tag set. From the editors’ console or the public interface, users can export a well-formed XML file containing catalog data and Person records. (Title records are scheduled for a later project phase). Download the TEI.

Creating Person Records

Stainforth’s catalog contains numerous examples of listing the same person in the catalog under different names (married, maiden, pseudonyms) or under variable spellings of the same name. Editors create a unique “person record” for each person in the catalog to connect different names and spellings that all belong to the same person. This also allows editors to more accurately quantify the number of people represented in the catalog, the number of authors who are findable in scholarship and library catalogs, and those who are not.

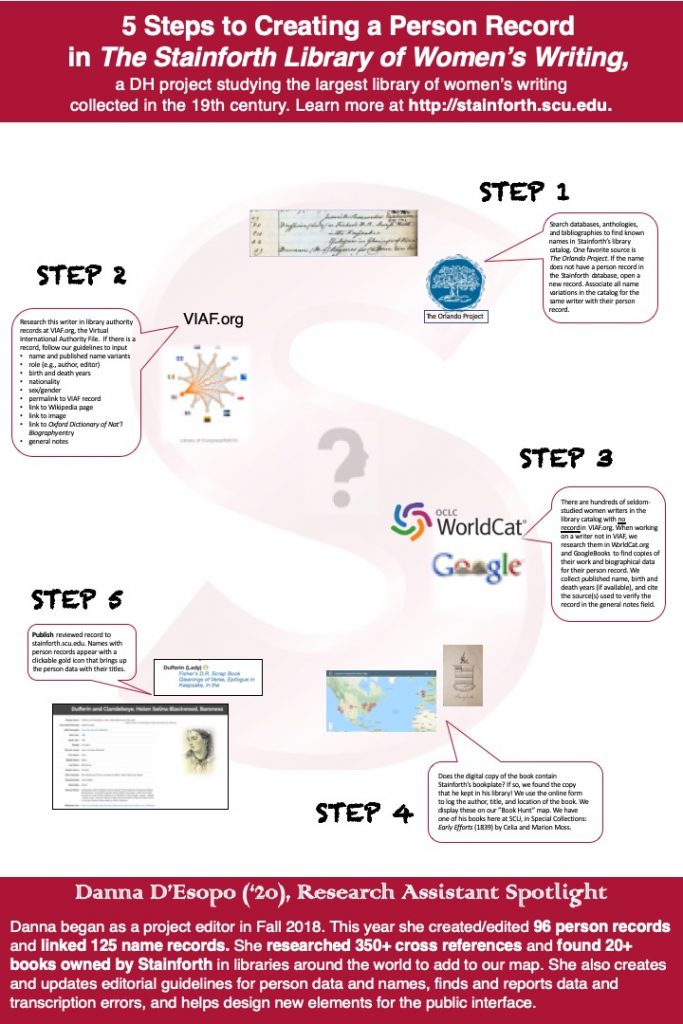

Here is an infographic about the process of making person records, made with Danna D’Esopo (SCU ’20) for a DH exhibit at SCU in Spring 2019.

- View our procedures for creating Person records here. [Note: these were our raw working/evolving guidelines for the project team. They have not been polished.]

To create these records, editors use the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF.org), The Orlando Project, The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and WorldCat.org as resources. Our team began the process of verifying the identity of each person listed in the catalog and creating “person records” or authority records for each author in our database. Each record contains the person’s name, as verified by two of the sources listed above if possible, role (e.g., editor, author, typesetter, co-editor), birth and death year, and nationality, for example. We also include links to their authority file in VIAF, their Wikipedia page, and their ODNB page, if available. As in our previous editorial stages, we pose any questions or points of confusion to the entire team for discussion and resolution via email or Slack.

Creating and Editing Name Authority Records in VIAF

In our person record research, we often come across authors who are missing name authority records that would help make them more easily findable in library catalogs. (See this LC page for information describing authority records.) A Name Authority record is a library catalog metadata file that establishes the officially recognized form of a writer’s name and makes her titles findable through library catalog interfaces. For marginalized authors, like women, having or not having an Authority record is the difference between having your work remembered and researchable, or forgotten. For example, because of a Name Authority record, books published with the pseudonym “The Milkmaid of Bristol” will automatically be connected to their proper author, “Ann Yearsley.” The Library of Congress (LOC) Names Authority File includes over 8 million records, and this is only one of the 50+ libraries worldwide that create Name Authority records through the Program for Cooperative Cataloging which comprise VIAF.org (Virtual International Authority File).

While it sounds like a minor search facet for names, a Name Authority record establishes an author in the library catalog as a unique, distinguishable person to which one can attribute their works, even those published under different names—a challenge unique to women writers who often published under maiden names, married names, and pseudonyms. To put it another way: if an author lacks an Authority record, it makes their titles difficult to find in library catalogs. Worse, it indicates that national and international library systems do not recognize them officially as a person or a writer as thoroughly as they recognize other writers who do have authority records.

One must be a NACO-certified cataloging librarian in order to submit Name Authority records to the Library of Congress and VIAF. Therefore, the Stainforth project partnered with Anna F. Ferris and Chris Long at University Libraries, University of Colorado Boulder. They have access to a running list of the authors we identify with no VIAF record, and they undertake the technical process, which can take months, to establish and publish approved records for them.

Cross-Reference Research and Linking

In Fall of 2019, we researched and encoded all 677 cross-reference entries in the catalog that tell a user to go “See” another name or a title entry in the catalog. Most of the cross-references connect an author name or title to another name. Only 12 of them have a target entry that is a title. We encoded each target in TEI to match the XML ID for each entry, which also matches its page and line number (page.line). For example, we added these new codes, in blue, to each entry:

L11 Amy of the Peak – See <ref target=”#p43.8″>Bingham</ref>

While researching these references to assign a target page and line number for each, we were surprised to learn that assigning target entries to cross-references is an interpretive act. In other words, each time we assigned a page and line number to a “See” entry as its target, we made an editorial decision. This is due to the number of types of cross-references that Stainforth provided as well as what they teach us. The types include:

- Specific entry-to-entry cross-references. These were low-hanging fruit. For example, page 4 line 6, “Affections Gift-See Hedge“. On page 200, line 19, there’s one clear intended target: “[Hedge (Mary Ann)] Affection’s Gift 1821”.

- General entry-to-name cross-references. Many references do not provide exact name-title targets but would instead point to a name that might have several titles listed beneath it. In these cases, we applied a rule to designate a “main” entry for that person, and the target would point to the top of that. How did we choose the main entry? We agreed that it was the earliest entry with the most different titles or editions listed underneath it. It will usually appear on the recto, but not always. For example, the name “Barbauld, AL” has the longest substantial list of editions on page 25, but she also has a substantial list on page 23 that one would miss, potentially, if the cross-reference went to page 25 and not 23. So, we specified the target for page 23 line 19, the top line on the earliest page.

- Cross-references that apply to multiple consecutive entries. Sometimes the target could be more than one line. In these instances, we used the same principle of assigning a “main” entry and picked the topmost recognizable target, since someone pursuing the cross-reference would likely see the other applicable targets just below. For example “C9 Johnson (E) 1696 – See Philomela” was assigned a target of page 391 line 21, though it applies to both lines 21 and 22 (the “ditto” line). Since the title is spelled out in line 21, it is more of a “main” entry for the cross reference, and a reader can easily find the reference below it since it is just the line below.

- If the cross-reference could apply to more than one line, give the line that is easiest for the user to find and that will help the user find the other lines that also apply.

- Where multiple entries might serve as the correct target, we narrowed this down to a single target if we found that the “See” reference and the target shared the same shelfmark. We used our shelfmarks chart to figure this out.