My co-editor, Debbie Hollis, recently shared with me Ann Yearsley’s library catalog, which one can access through Gale/ECCO.

My co-editor, Debbie Hollis, recently shared with me Ann Yearsley’s library catalog, which one can access through Gale/ECCO.

Go to Ann Yearsley’s Library Catalog

My current institution doesn’t subscribe to ECCO, and I took this incredible (and expensive) database for granted at both CU-Boulder, where I did my PhD, and at Dartmouth College, where I was a postdoc. I mention my access issue in this post because I’m currently writing an exercise that helps students recognize the differences between institutions’ various library catalogs and how blind spots and access issues only reveal themselves when we can draw critical comparisons between interfaces, collections to search, cataloging systems, and levels of accessibility. I’ll include a link here to the completed exercise when it’s ready. Yearsley’s library catalog is not shy about issues of money or access. It makes the business-side of libraries, and the cost of goods, clear.

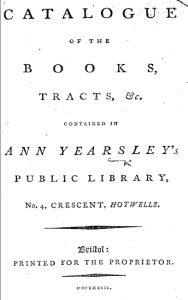

Yearsley’s library catalog was printed in 1798 “For the Proprietor” (presumably Yearsley) in Bristol. Below her name, on the title page, it indicates that this is a “public library.” The catalog differs substantially from Stainforth’s in its smaller size, at 37 pages, and in its mission to execute the business of her library. Open the catalog and the first page contains not titles but subscription rates and rules or “conditions,” as she calls them, for membership. Subscription rates were 1 pound per year, 1/2 pound per quarter, or .26 pounds per month. The very first rule is “The Money to be Paid at the Time of subscribing.” If you ask me what her first cataloged item is, I would say “Money.” The following three conditions are similarly stern and businesslike:

- Subscribers must give their names and home addresses and the value of the books they borrow. If they lend their books to non-subscribers, they forfeit their subscription. (3)

- If a subscriber writes in a book or damages “a Leaf” while in their custody, they must pay the price of the book or set of books listed in the catalog. (3)

- If a subscriber keeps a book beyond the paid-for length of subscription, they are deemed to be continued subscribers and must pay for a renewed subscription.

- [Worst of all] If a subscriber loses a book, and their subscription lapses, they are still subscribers and still owe for their subscription and the price of the book, as stated in the catalog, until all is paid. (4)

After the rules, Yearsley lists her books. She assigns each volume a number, presumably to keep track of the books and also perhaps for shelving purposes. The first volumes are writings by the ancient Greek philosopher Anacharsis, followed by Gibbons’ Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and shortly thereafter Travels through Syria and Egypt by Volney and more travel writing of Asia, England, North America, Spain, and more. On page 8, the first literary works appear, including Honoria Somerville, A Novel co-written by Jane and Elizabeth Purbeck, little-known Romantic authors who I look forward to learning more about. A perusal of the rest of the catalog shows that the listings are often by title, they don’t include publication dates, and there are lots of “Ditto” marks, since nearly every title has more than one volume. Fittingly, the catalog ends with a listing for three volumes of “Poems, by Ann Yearsley” (37).

Yearsley’s catalog reminds me not only of the expense of libraries, as in the cost of ECCO that I previously took for granted, but also of how hard I am on my books as well as those I borrow. I toss them in bags, drop them, write all over them (on sticky notes), flag them (and de-flag when I return to the library), read them while eating runny eggs and bacon, lose them behind couches and find them later, my cats sit on them and chew their pages despite my best efforts to protect them, and more torture. Yearsley’s small public collection could never be handled the way most of us handle books without our constantly paying late fees and for replacements. (That is, unless she was bluffing in her stern list of conditions.) Her catalog is also very difficult to search. It seems to start with classical Greek writings and moves into literature with some alphabetical progression by author or title, but I did not discover the exact ordering principles of the catalog. I paged through it to find things.

I look forward to learning more about her library primarily because it shows her to be so enterprising and to contribute to the book business as more than a poet recognized merely as “Hannah More’s protégé” or “Lactilla” or “the Bristol Milkwoman.” Orlando reports that she “set up her circulating library in 1793 in The Crescent, also called The Colonnade, at Bristol (near Bristol Hot Wells). Her circulating library was in fact a success, though almost all sources until recently have said the opposite. Through it and her literary ventures she probably made enough to set up her one surviving son in business. She gave up her library about 1797, perhaps because of ill health.” I was glad to read that she likely made some money.