In 2019-2020, we completed the project of counting the editions in the library catalog, and we concluded that there are 7,122 editions. This month, after completing a massive multi-year effort to editorially address every name in the catalog listed as an author, our most recent counts tell us that there are:

- 3320 names listed in the catalog as authors/editors/translators

- 2814 total person records in the database, created by editors to describe the names.

- 1215 fully researched person records verified with credible sources (read more about the process of making full person records here)

- 1599 short person records

- 118 entries with titles that include the phrase “by a lady”

What do these numbers mean and why do they matter? Here are some preliminary thoughts.

The number of total person records compared to the number of names in the database tells us that 15% of the names in the catalog were spelling variants of the same person’s name or were different names (e.g. maiden name, pen name, married name) for the same person. Where more than one name record applies to a person record, we create hard links between them. That is a lot of women listed severally with alternative spellings, maiden names, pseudonyms, cross-references, and more. These spelling variations and multiple names have traditionally made women harder to research and more challenging for editors and librarians to make these people findable. (See related posts on disambiguating identities here and here.)

Our figures also show that there are 384 more short person records than there are fully researched person records. For 1215 of the people (mostly women) in the library, editors were able to verify their identities with relatively straight-forward research in established databases, bibliographies, and/or anthologies. In 1599 cases, we had to make short person records, or records that acknowledge that more research is needed on this person to complete a full person record. In most cases, a short person record signifies that the name was very difficult to research and verify in relation to the title(s) in the catalog entry, and in some cases it signifies that we simply need to come back to a person to complete the work. Therefore, the library catalog appears to have 300 or more people that are less readily researchable compared to the more established authors who have full person records. I was concerned about this disparity as a shortcoming of our editorial team–that we have full person records for fewer than half of the total number of authors in the catalog–until I realized that it reflects one of the major facts that this library reveals. That is, there are far more women writers who have published between the 16th and the 19th centuries than scholars have studied and published on, especially in the genres of poetry, drama, and devotional literature. Of course we had trouble fully researching all 2,814 of them.

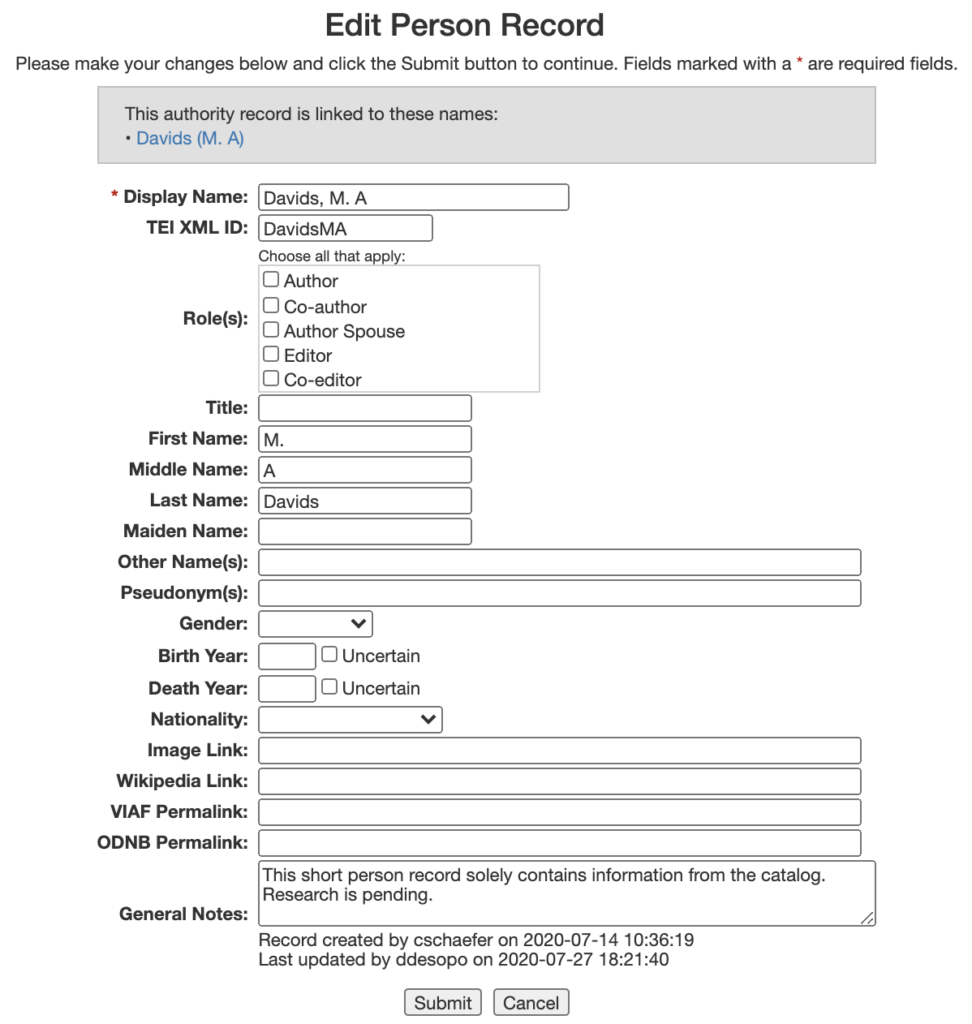

The differences between a short person record and a full person record are several, and they’re easy to see if you compare the records. Below is an example of the short person record for Davids, M. A, who appears to have only one entry in the catalog: Ms. Verses (1833) (page 122, line 11). Since we were unable to find a secondary source to confirm Davids’ identity linked to this title, we created a short person record that uses only the data given in the manuscript to create the entry. A very crucial part of this entry is the General Note that explains “this short person record solely contains information from the catalog. Research is pending.” This note is repeated verbatim in every short person record. We intend the note to convey that more research is needed on this author’s record, it is a work in progress, and in the meantime the author deserves at least a placeholder record to help make them findable. The alternative would be to not give Davids even a short person record, which would only make the already obscure author/title even harder to find, since the easier-to-research people and titles all have full person records. Denying Davids a person record would say, in essence, primary source evidence of your existence as a writer doesn’t matter; you’re not historically relevant unless you’ve been previously cataloged and/or published about. This would undo so much of the work the Stainforth project tries to do to make unrecognized authors and titles findable.

I want to amplify this catch-22: you generally have to already be researchable–that is, have entries in scholarly sources/databases–in order to gain an entry in a new scholarly source. If you are not researchable in scholarly sources, it is far less likely that you will gain a foothold in a new scholarly source. Scholars like to cite from and pull from the sources they have access to. Discovering who or what you don’t know that you are missing is much harder. By making short person records even for those writers we were unable to research in other pre-existing scholarly sources (e.g. databases or anthologies), we are enlarging the findable, searchable scope of literary history.

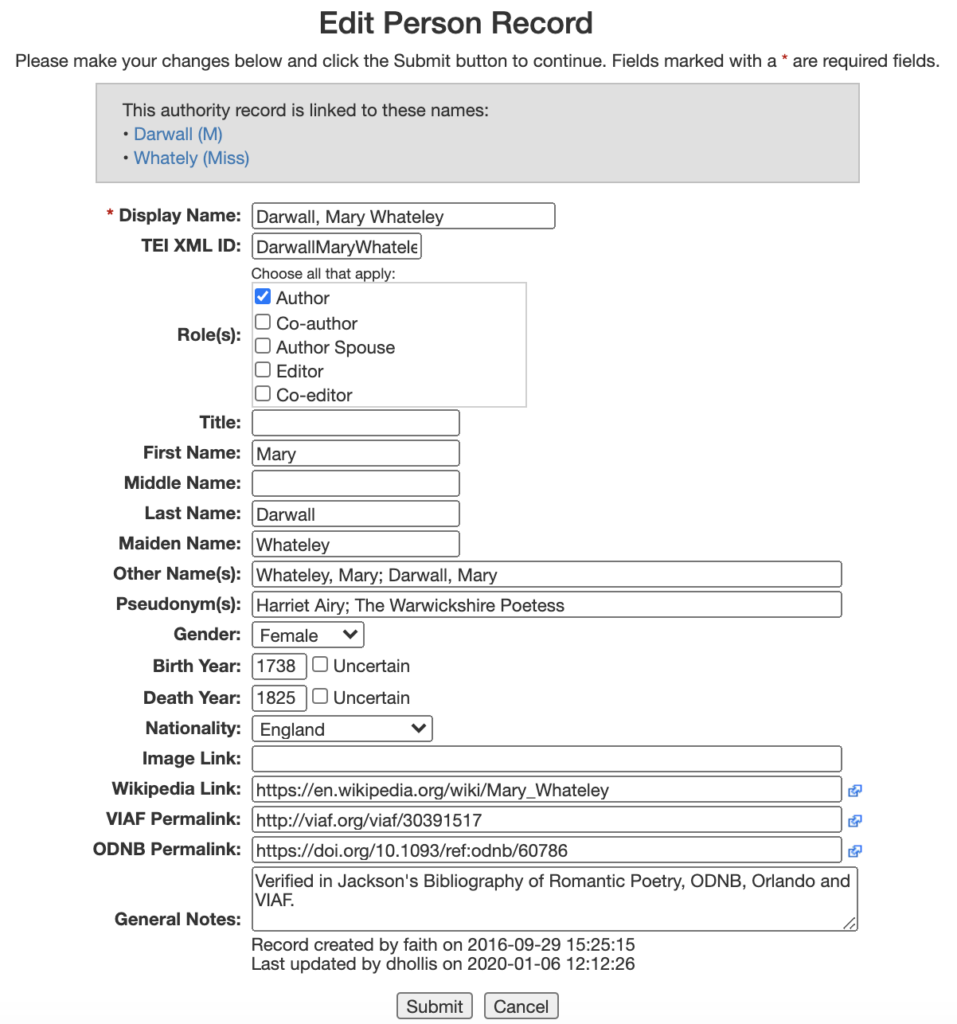

Contrast the short person record with this full person record for Mary Whateley Darwall:

In this record, the General Notes field again tells us, crucially, that the data in this record came from J. R. de Jackson’s Bibliography of Romantic Poetry, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Orlando, and viaf.org, four authoritative scholarly sources. Darwall’s person record was, compared to Davids’, much easier to research or, as Stainforth editors would call it, low hanging fruit. Her record was first researched and created by Faith Escobado, an exemplary former editor, in September 2016 in one of the first years of person record creation work.

One more thing the numbers teach us is that approximately 120 people in the catalog are identified in their catalog entries and on their title pages as “by a lady.” See the results of a “by a lady” title query here.) In just a few of these cases, Stainforth provides a cross-references that debunks the mystery of the author’s identity, but in nearly all cases we don’t have biographical data or even a name to pair with the title.

The next big phase of project development will focus on collecting data for editorial records describing the titles mentioned in the library catalog. This will be especially helpful for adding context and detail to records “by a lady.” In the meantime, we are constantly refining our person data, and editors have begun trying to research short person records where there is potential to research a full person record. The numbers at the top of this blog post will probably change. If you would like to explore our data, you can download our digital edition and person data as a TEI file.

Some updated stats as of May 27, 2021

Total Person Records: 2816, including Short Person Records

Person Records for which we could not find a VIAF: 1710 (includes SPRs)

Person Records with VIAF links: 1106

Total Short Person Records: 1347

Person Records that have been fully researched (not SPRs) = 1469

Fully Researched Person Records with no VIAF were were able to locate: 363, or 24.7%