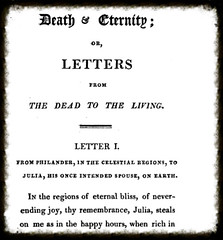

Ann Maria Ainslie does not have an Orlando Project entry or a Wikipedia page, but Francis John Stainforth collected the second edition of her volume Letters from the Dead to the Living; and Moral Letters, published in Edinburgh in 1812. In fact, you would not know what an interesting title this is from Stainforth’s ms catalog listing, which simply says “Ainslie (A. M) Letters +c. Edn. 1812.” (You can also find her poem “Sonnet:–The Maniac” as well as “The Rose” in Dec. 1810 Edinburgh Monthly Magazine. The latter was written when the poet was 14.) Here is a small stub on her entry that helps to at least put her name and this title on the map. The chapter titles in this collection of letters tug at the heart. I immediately wanted to read letter VI “From an African Slave to His Wife,” and secondly Letter V “From Adelaide to Fernando,” because the names are so oddly specific. The letters put the reader of the volume in the position of the living loved one who is astounded to receive a letter from his or her beloved deceased. I admit that I expected this to be a poetry volume, but it contains letters in both poetry and prose. While they contain some details, these short pieces are fairly light on name/time/place specifics, and they fail to seem realistic; with that, they lose some punch. Indeed, they are made-up tales that warn readers about the horrors of dying outside the Christian faith. These stories are literary scare tactics, and they evoke children’s literature meant for moral instruction played to the tune of adult-level grief. Indeed, if she was 14 in 1810, then she was merely 16 in 1812, the publication date on this volume

Start not, Fernando, at the well known hand writing. It is a proof that thou art yet cherished with fond remembrance; my passion for thee, pure and innocent as the breath of Heaven, burns still ardent in the immortal soul. I have, unseen, beheld thy grief for my death, and heard thy frantic exclamations of despair. To inculcate the necessity of resignation to the decrees of the Most High, I am permitted to address thee from the mansions of the blessed. (47)

The husband in the African couple tells the story of their short stint enslaved together, but that they were subsequently sold to separate masters. The event of their separation is graphic and upsetting:

Thy heart rending shrieks, thy supplicating arms stretched towards me, raised in my breast the frenzy of despair. I would have released or died with thee, but numbers overpowered me; I was secured and carried off impotent–we met no more!

After a series of ownership changes, the husband meets a priest, converts to Christianity, and is baptized. Then, he dies, and after death he is gloried by seraphim who clothe him in holy vestments as well as light. He finds his wife in the land of the living, disguises himself as Azid the angel, whom she would recognize, and tries to help her understand that freedom lies in death and a return to God’s kingdom, while life enslaves her, literally. Similarly, Rodolpho tells his sister, Jacintha, that he murdered their father (with poison), and that it is not a desirable path to follow him. He was dragged into the “fires of perdition,” and he is allowed to tell his story to Jacintha to help protect her from his own ends (67-75). In comparison to letters from the dead that instruct readers to follow Christianity, the moral tales that follow seem watered down.